Tesla’s fall from status symbol to a social liability

The story of its decline is a behavioral norms case study unfolding in the wild

By now, we’ve all seen the headlines: Tesla’s stock price is sliding, its sales are shrinking in key markets, and its once-loyal customers are distancing themselves—sometimes literally, with bumper stickers that read “I bought this before Elon went crazy.”

The usual analysis stops there. A rich CEO becomes polarising; some people protest; sales dip. But what if that’s not the whole story? What if this isn’t just a reputational crisis? What if this is a case study in how social norms shift—in real time, across networks, via digital and physical coordination—and how those shifts can radically alter consumer behaviour?

To follow that thread, we need to look beyond boycotts and branding. We need a deeper map of the social terrain. That means borrowing a sharper conceptual lens—namely, Cristina Bicchieri’s work on the dynamics of social norms.

What emerges is a more sophisticated story about the power of grassroots movements, norm entrepreneurs, and coordinated expectations to change not only what people do, but why they do it.

Before we jump in, you may want to listen to this deep dive into the theory!

Ep. 6: Deep Dive into Social Norms

What do we really mean when we say something is a social norm? And why do some norms hold on—even when nobody seems to like them?

The social physics of backlash

Most articles treat norms as statistical averages, but Bicchieri’s work insists that social norms are more than observed behaviour—they’re conditional expectations. People conform to norms not just because others behave a certain way, but because they believe others expect them to behave that way, and that there is some form of social sanction or reward for doing so.

Apply that to Tesla, and a clearer pattern emerges. We’re seeing a powerful shift in both types of expectations:

Empirical expectations: More people are publicly disavowing the brand.

Normative expectations: People believe their peer networks expect them to act accordingly—whether that means selling, shaming, or showing solidarity.

The result isn’t just a reputational problem. It’s a realignment of behavioural incentives for consumers embedded in networks that now see owning a Tesla as not just embarrassing, but morally suspect.

In social norm terms, this is normative spillover in action:

Musk’s actions in politics (e.g. alignment with far-right movements, involvement in DOGE) have triggered moral outrage.

That outrage has “spilled over” onto the brand’s products, even though the cars themselves haven’t changed.

In Bicchieri’s language, this is an example of a norm being reclassified from a context-specific expectation (“I should buy electric”) to a broader moral stance (“I should not support companies aligned with authoritarianism”).

This shift is especially destabilising when the product in question is a status symbol. Brands that once conferred virtue can rapidly lose their social utility when consensus approval fractures. If owning a Tesla once signalled moral virtue, it now may signal political naïvety—or worse.

Bicchieri also emphasises that norms don't exist in isolation. They’re embedded in reference groups—those whose approval or disapproval we care about. In Tesla’s case, the eco-conscious, left-leaning, tech-savvy consumer segment once lionised Musk. But as his alignment with the Trump administration and the far right intensified, these groups began to fracture.

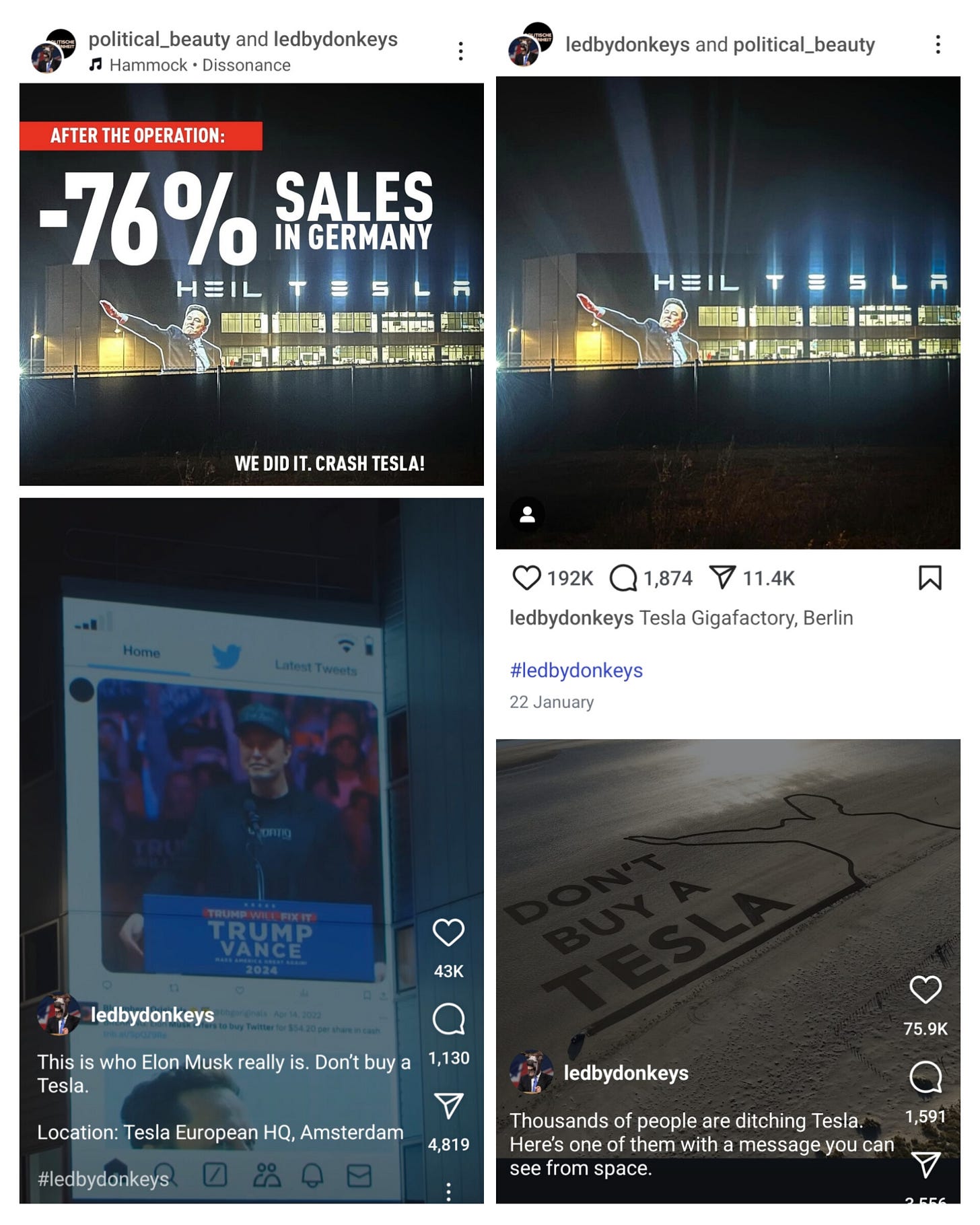

Activists and norm entrepreneurs exploited this fracture, using digital tools (hashtags like #TeslaTakedown and #Swasticars) to:

Signal new empirical expectations (Look, lots of us are angry).

Create new normative expectations (If you care about the climate or democracy, don’t buy a Tesla).

Build salience via public rituals of defection—selling a car, adding protest stickers, burning charging stations (in extreme cases).

Visibility, virality, and norm cascades

So how do these private frustrations become public action? Social norms do not emerge in silence—they thrive or die by being seen. Cristina Bicchieri’s work highlights that the power of a norm lies in its conditionality. We conform when we believe others are conforming and expect us to do the same. But what determines when these beliefs shift? Visibility. And in the networked age, virality.

From private beliefs to public signals: In the early days of the backlash against Tesla, personal discontent remained largely private. Consumers unhappy with Musk’s politics or Tesla’s perceived ideological drift may have grumbled in silence. What changed was the transformation of these private frustrations into visible acts: owners posting videos of them peeling off Tesla logos, adding “I bought this before Elon went crazy” bumper stickers, or dramatically announcing their vehicle sales online.

Such behaviors are not mere expressions—they are public signals that invite coordination. Bicchieri's theory suggests that individuals are not just passive recipients of norms, but active watchers. We scan our environment for cues, especially from those we perceive as similar or influential, to determine what’s acceptable, expected, or worthy of emulation.

Hashtags as norm amplifiers: In this context, hashtags like #TeslaTakedown and #Swasticars operate as digital accelerants. They aggregate individual acts into a perceived collective movement. A single protest outside a dealership might go unnoticed, but framed within a viral campaign, it becomes evidence of shifting expectations. Social media users encounter not just behavior, but interpretations of that behavior (commentary, moral framing, and emotional tone) which are critical to norm activation.

Eventually, this reaches a tipping point. What we are witnessing is a form of norm cascade: the moment when public signals become strong enough that those on the margins revise their beliefs about what others think and do. As more people observe disapproval of Tesla being enacted and amplified, especially by peers or aspirational figures (e.g. Sheryl Crow publicly divesting), it becomes safer—and perhaps even expected—to do the same.

Virality and network effects: Crucially, this dynamic does not spread evenly. Norms propagate most quickly through dense, homophilous networks—people who share similar values, identities, or lifestyles. Among progressive, eco-conscious consumers—the very market Tesla once dominated—the backlash has moved with notable speed and cohesion. Here, shared identity magnifies the credibility of observed behavior. One post from a green-tech influencer or activist doesn't just inform; it licenses imitation.

That’s why visibility matters more than volume. Grassroots campaigns often prioritise getting the right people to defect—loudly. The perception of consensus begins to shift not when everyone acts, but when a few key figures do so in ways others can see and interpret.

Reframing Tesla’s market status through collective action

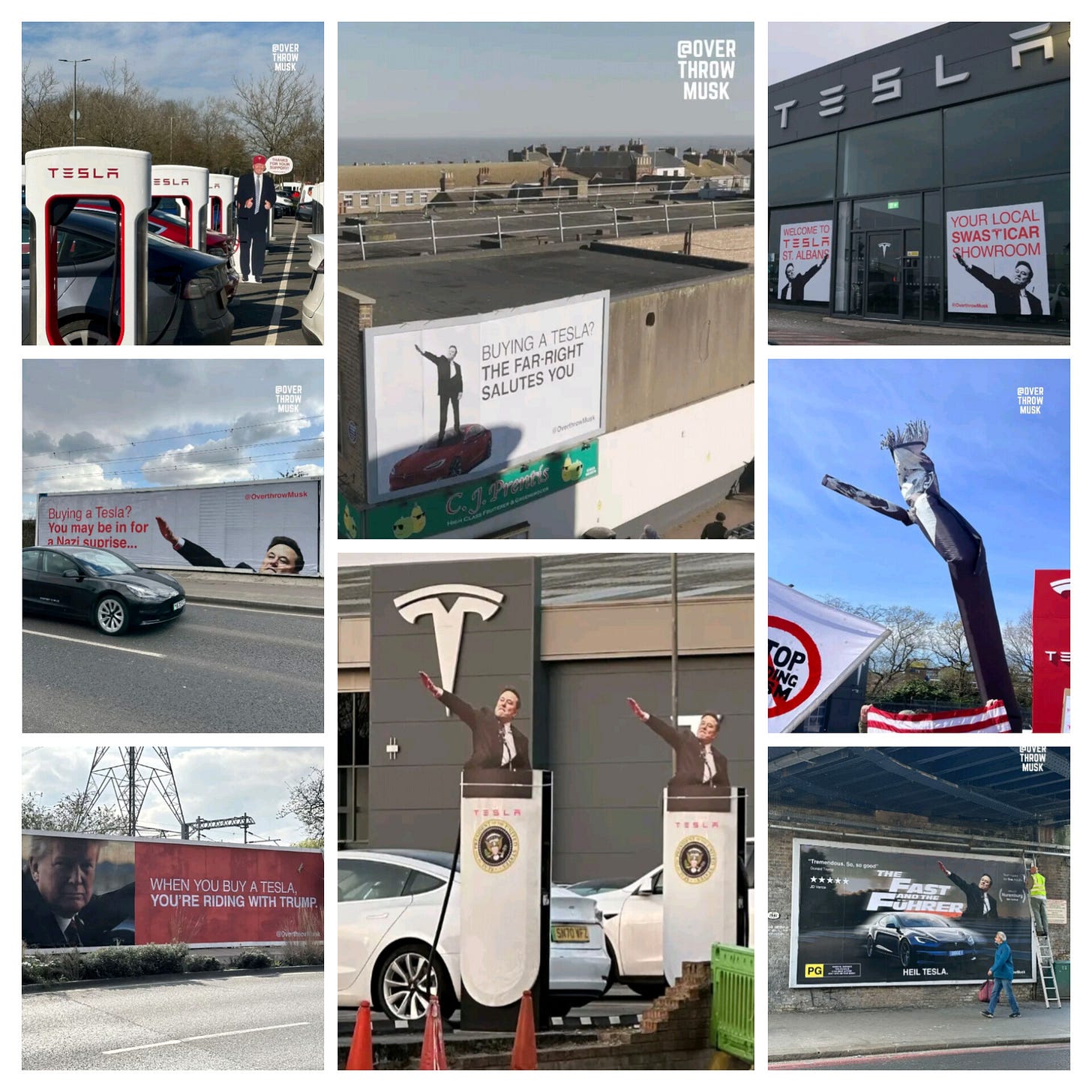

This isn’t just social—it’s strategic. Elon Musk’s wealth and visibility have long insulated him from traditional forms of accountability. But norms, unlike laws or regulations, operate through a different kind of enforcement—one rooted in social perception, reputational contagion, and coordinated withdrawal of support. Activists have not merely been protesting Tesla; they’ve been reframing it.

Social norms as economic pressure: Bicchieri’s framework reminds us that norm compliance isn’t just about shared beliefs—it’s about shared expectations. In this case, the campaign against Tesla is fundamentally about undermining the normative legitimacy of being a Tesla owner. The goal is not just to discourage purchase—it is to make owning a Tesla feel like complicity.

The psychological mechanism here is norm-based disutility: the discomfort that arises when one’s actions conflict with emerging social expectations. As online posts mock Tesla drivers, label the cars “Swasticars,” or imply that driving one is a political statement, the cost of ownership becomes symbolic, not just financial.

Selling a Tesla, in this context, becomes identity maintenance. Bumper stickers that say “I bought this before Elon went crazy” are not jokes; they are public declarations of non-allegiance.

The logic of reputational sanctions: This strategy draws on a powerful behavioral mechanism: reputational sanctioning. When formal punishment is impossible—how do you “punish” a billionaire?—grassroots actors often turn to market-based social penalties. The goal becomes clear: create conditions in which Musk’s companies lose their social licence to operate among key demographics.

In practical terms, this has translated into coordinated actions to suppress Tesla’s valuation. As discussed on social platforms, activists have explicitly stated that dropping the stock price is the only way to materially impact Musk, who is otherwise “untouchable.” This reframes market actions—selling stock, boycotting cars—not as passive disapproval, but as instrumental forms of protest.

This is how norm change hardens into obligation. The idea echoes what Bicchieri calls normative entrenchment: when enough people align around a behaviour not merely because they prefer it, but because they believe others expect it of them. In this sense, the protest has moved beyond expressing dissatisfaction to creating obligation—particularly for progressive consumers who previously saw Tesla as an ethical choice.

Recasting ownership as deviance: Tesla ownership, once a status symbol of environmental and technological progress, is being rebranded as a signal of political misalignment. What we are seeing is a reversal of the informational function of consumption: products no longer say “I’m green and forward-thinking,” but “I’m tone-deaf or complicit.”

This is particularly potent in digital spaces, where signalling is amplified and monitored. Public statements like “I sold my Tesla and donated the proceeds to NPR” aren’t just acts—they are invitations to others to follow suit, creating a new norm of expressive defection. The broader goal is clear: isolate Musk reputationally, and drain the moral capital from his brand ecosystem.

Identity, reference networks, and the contagion of norm-driven behaviour

Bicchieri’s work also draws a crucial distinction between what people personally believe and what they believe others expect of them. When trying to change collective behaviour, it’s not enough to shift individual preferences. You must shift the expectations embedded in social networks—especially those that shape identity and belonging. This is precisely what’s unfolding in the Tesla backlash.

The power of reference networks: A reference network is the group of people whose opinions and behaviours matter most to an individual. They are the audience whose judgment carries weight—friends, colleagues, online communities, public figures. As Bicchieri puts it, norms don’t live in the abstract; they live in specific communities.

For progressive consumers, environmentalists, or technophiles who once embraced Tesla as an ethical brand, the reference network has changed. Once, the salient norm was: “Buying a Tesla signals climate commitment and tech-savviness.” Now, the same action risks being interpreted as: “You support Musk’s politics, or you’re out of touch.”

In short, the network has flipped the meaning of the signal. This shift is turbocharged by social media, where users see not only what others are doing, but what others approve of. The visible distancing by public figures like Sheryl Crow, the proliferation of memes mocking Tesla ownership, and grassroots campaigns like #Swasticars all provide real-time cues about what behaviours are becoming socially costly or rewarded.

Identity alignment and the threat of norm mismatch: People tend to conform to the norms of groups with which they identify. And when those group norms change, individuals face a dilemma: change their behaviour, or risk social misalignment. For example, a progressive climate advocate who drives a Tesla now finds themselves caught in what social psychologists call identity dissonance. The product that once aligned with their values is now a source of reputational risk.

This is where norm cascades can begin. When a few prominent individuals defect from a behaviour—publicly selling their car, switching allegiances, or adding “anti-Elon” bumper stickers—they offer others a script for doing the same. Normative uncertainty becomes resolved: it’s not just okay to leave Tesla behind; it’s expected. This is how identity and network effects turn private discomfort into public action.

Network density and the speed of norm shift: Social networks also differ in how tightly connected their members are. In high-density networks—such as activist communities, subreddits, or professional circles—the speed of normative updates is faster. This is why resistance to Tesla has spread so rapidly in certain cultural pockets, even while remaining muted in others.

This dynamic creates localised norm clusters: in some regions or digital communities, Tesla ownership is still neutral or aspirational. In others, it is already stigmatised. These clusters can coexist for a time—but as the protest gains visibility and momentum, the tipping point comes when enough people believe most others in their network expect a certain behaviour. That is the essence of a conditional norm, and it explains why Tesla’s challenges are no longer just about politics, but about belonging.

Norms, stigma, and the role of negative signalling

Social norms are not static—they can flip. What was once virtuous can become deviant, and vice versa. Cristina Bicchieri’s framework is especially helpful here: a behaviour governed by a descriptive norm (“everyone is doing it”) or a social norm (“people like me expect me to do it”) can become taboo when the underlying expectations shift. We are now witnessing such a reversal in the case of Tesla ownership.

Stigma and symbolic pollution: Once an object of eco-status and tech-progressivism, the Tesla badge is being recoded in parts of society as a political symbol. Not merely a car, but a marker of association—with Elon Musk, with anti-woke politics, with authoritarian-adjacent governance via DOGE.

This is how symbolic pollution works: a product becomes morally contaminated by association, and continued ownership elicits reputational risk. Stickers like “I bought this before Elon went crazy” or “Anti-Elon Tesla Club” are not jokes—they are negative signalling devices, attempts to pre-empt judgment and reassert moral alignment. It is the same mechanism by which individuals in divided societies wear visible cues (badges, hashtags, disclaimers) to distinguish themselves from disliked out-groups.

Harassment and the enforcement of new norms: Norms are not enforced by laws—they are enforced by people. In this case, by other drivers, peers, and digital onlookers. Tesla owners now report being brake-checked, flipped off, or confronted in parking lots. This is not random aggression. It is a form of norm enforcement through social sanctioning.

Bicchieri argues that for a social norm to take hold, people must (1) believe others follow the behaviour and (2) believe others expect them to follow it. Public sanctions are one way this expectation is communicated. This is particularly potent when the sanctioner and the sanctioned inhabit the same reference group—say, progressive climate-conscious consumers. A dirty look from a peer matters far more than one from a stranger.

Status loss and the inversion of prestige norms: Tesla’s original appeal rested on a fusion of prestige and purpose: to drive a Tesla was to signal environmental commitment and financial success. That dual signal was powerful, but when a behaviour flips from norm-compliant to norm-violating, the status signal reverses. What once elevated the owner now invites ridicule, and the silent car is now a loud statement—only now, the statement reads as selfish, tone-deaf, or complicit.

In social norm theory, such inversions are rare but once triggered, they can be swift and sticky. Owning a fur coat, for instance, or lighting a cigarette indoors, once denoted status. Today, in many circles, they elicit disgust. The Tesla may be entering similar territory in select identity clusters.

Strategic norm entrepreneurship

Of course, not all change is organic. Often, it is driven by what Cristina Bicchieri calls norm entrepreneurs: individuals or groups who deliberately attempt to shift collective expectations. In the case of Tesla, activists are crafting a coordinated attempt to redefine what the car represents, using stigma, humour, and network dynamics as their levers.

Movements like #TeslaTakedown are not spontaneous outbursts—they are strategic interventions. These are designed to create expectation cascades—moments when people suddenly realise others disapprove of a behaviour they once thought was acceptable.

Activists are deploying a playbook drawn from behavioural science, whether consciously or not. Key tactics include:

Guerilla marketing (e.g. subverted bus stop ads in London) to generate viral disgust

Meme warfare and hashtags like #Swasticars to emotionally rebrand the product

Shaming and performative selling (e.g. public Tesla resale posts) to shift perceived norms

Symbolic protest at showrooms and factories to create visible dissent

Publicising celebrity disavowals, like Sheryl Crow’s donation, to create reference-group signalling

Each of these serves to destabilise the perceived normality of Tesla ownership, prompting bystanders to question their own stance and perhaps disidentify with the brand.

Stigma and the social status death spiral

At this stage, it’s not just a backlash—it’s a full-blown identity crisis. Status brands like Tesla operate in an identity economy. Their value is not just in performance or aesthetics, but in what they signal about the person who owns them. When those signals shift, especially toward moral disapproval or social stigma, the brand's cultural capital can collapse faster than its market cap.

Tesla’s original appeal rested on moral signalling: climate leadership, design elegance, and innovation. It was a badge of progress. But Musk’s increasingly controversial political affiliations and his association with authoritarian and alt-right movements have contaminated that signal. Owning a Tesla, once shorthand for environmental virtue, is now seen in some circles as complicity or carelessness.

This is where Bicchieri’s model and moral psychology converge. We are witnessing a reclassification of Tesla from a positive norm-compliant behaviour to one increasingly perceived as a norm violation within certain reference groups.

Moral psychology research (e.g., Rozin’s work on contagion and “moral taint”) shows that once something is perceived as polluted, association alone can trigger disgust or avoidance. We see this now with Tesla ownership:

Drivers adding disavowal stickers aren’t just joking—they are norm-hedging, trying to inoculate themselves against reputational contagion.

Resale narratives (“I bought it before Elon went crazy”) are not logistical decisions—they’re identity repairs.

Online ridicule—like the memes comparing Teslas to “Swasticars”—reinforces this contagion effect, especially in politically progressive circles.

Status is sticky—until it isn’t. Status is a social currency, and once devalued, people offload it quickly. As high-status individuals or influencers disassociate, a tipping point looms. Bicchieri’s model predicts that when a norm violation becomes widespread enough, compliance becomes irrational—even for those who still value the original product. In other words, people might sell their Teslas not because they dislike the car, but because they dislike what the car now says about them. This is a norm cascade in reverse at speed—and when norms are backed by moral emotion, they spread fast.

A case study in contested norms

What began as scattered discontent has become something else entirely. It has coalesced into a multilayered campaign that strategically deploys the mechanics of norm change: shifting expectations, reframing identities, and engineering public visibility.

Through the lens of Cristina Bicchieri’s social norm theory, we can see that Tesla’s declining fortunes are the product of calculated interventions aimed at reshaping what people believe others believe. This isn’t just branding warfare—it’s behavioural architecture. The campaign against Tesla has weaponised everything from hashtags to shareholder pressure, harnessing the power of grassroots norm entrepreneurship to turn cultural prestige into reputational risk,

It also reminds us of something more fundamental. Norms are not static: they are social equilibria held in place by mutual expectations, and they are vulnerable to those who know how to shift the scaffolding beneath them.

It also shows what happens when those actors are agile, networked, and media-savvy—and when a brand becomes more than a product: a proxy for broader social conflict.

The Tesla takedown is not just about one man or one company. It is a masterclass in how norms move. And perhaps, in a world where identity, politics, and consumption are ever more entangled, that movement is the story of our time.

Sources: Bicchieri, C. (2016) Norms in the wild: How to diagnose, measure, and change social norms.; Bicchieri, C. (2006) The Grammar of Society: the nature and dynamics of social norms.

Video compilations of social media posts: