What happens to science when words like "bias" get banned from research?

New U.S. restrictions on research language threaten to reshape global scientific progress - including behavioral science

Imagine trying to study how people make financial decisions without being able to discuss socioeconomic background, or doing research on moral reasoning in different countries without using the term "cultural differences." This is the reality behavioral scientists now face under new U.S. government restrictions on research language.

N.B. This isn’t the usual content of this Substack, but given the unexpected and far-reaching impact of these new restrictions, it seemed important to address!

What’s going on?

In February 2025, the U.S. government issued executive orders restricting federal funding for research related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). The National Science Foundation (NSF) is reviewing over 10,000 existing grants, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has temporarily paused its grant review process.

While these policies claim to target DEI programs, their implementation affects core behavioral science research. Studies examining decision-making patterns, cultural influences on behavior, and economic psychology face increasing constraints—not because they lack scientific merit, but because the language used to describe them has become politically sensitive.

TL;DR - If researchers avoid studying certain topics or populations simply because their proposals contain "suspicious" words, it undermines our ability to generate real-world insights, making science less representative and useful, and risks setting medical and behavioural science back decades.

How language shapes research design

Scientific progress depends on precise terminology. In behavioral science, terms like “bias,” “cultural norms,” and “socioeconomic status” define measurable constructs essential for studying human decision-making. Yet, under the new policies, federal agencies are now forced to flag grant proposals containing certain terms for additional scrutiny. This would force researchers to make difficult choices:

Replace scientifically precise terms with vague alternatives which weakens clarity and replicability

Reframe research questions to avoid flagged language by altering study design for political rather than scientific reasons.

Abandon certain lines of inquiry entirely which reduces the scope of (behavioral science) research

For example, a study on financial decision-making among low-income populations might traditionally examine how “socioeconomic background” influences risk preferences. If that term is flagged, researchers might opt for less precise wording, making results harder to compare across studies. These restrictions don’t just affect funding—they shape what questions are asked, how experiments are designed, and ultimately, what knowledge is produced.

Impact on methodology and measurement

Behavioral science relies on precise terminology to measure cognitive and social processes accurately. When key terms become politically sensitive, measurement validity is compromised, limiting researchers' ability to study human behavior effectively.

Consider these challenges:

Implicit bias and stereotype research: The Implicit Association Test (IAT), a key tool for studying bias, prejudice, and stereotypes, depends on clear definitions of these constructs. If research proposals using these terms face additional scrutiny, studies on discrimination, group identity, and social influence could be stalled or defunded.

Decision-making under uncertainty: Studies on cognitive biases, such as loss aversion and framing effects, help explain financial choices and risk perception. If researchers must avoid discussing biases directly, they may struggle to study real-world decision-making accurately.

Socioeconomic influences on behavior: Economic psychology and social mobility research rely on terms like socioeconomic status to examine access to resources, financial decision-making, and opportunity gaps. Restrictions on this language could obscure critical drivers of behavior, reducing the effectiveness of financial literacy programs and policy interventions.

Gender and sense of belonging in the workplace: Research on workplace behavior, team dynamics, and leadership relies on studying gender diversity and sense of belonging. If these terms are restricted, organizations may lose valuable insights into improving team cohesion and performance.

Polarization and misinformation: Studies on political and social polarization are essential for understanding group dynamics, media influence, and public trust in institutions. If researchers must avoid discussing historical patterns of division, efforts to combat misinformation and social fragmentation may be weakened.

These restrictions don’t just affect funding—they reshape what behavioral scientists can measure, how they design experiments, and whether their findings can be replicated across studies. When key constructs are removed from the research process, the field’s ability to produce reliable, applicable knowledge is severely diminished.

Effects on cross-cultural behavioral science research

BeSci has been disproportionately based on WEIRD populations but we were finally starting to make progress in incorporating diverse perspectives - including non-Western cultural influences, and structural inequalities. Today, studies increasingly examine how economic conditions, social structures, and cultural norms influence behavior. However, the current restrictions threaten this progress:

Choice architecture across cultures: How do framing effects vary between collectivist and individualist societies? If “cultural differences” becomes flagged language, researchers may struggle to frame these studies within funding constraints.

Social norms and cooperation: Studies on trust, reciprocity, and cooperation depend on measuring cultural variation. Removing explicit discussions of cultural influences limits our ability to understand what drives prosocial behavior.

Scarcity and decision-making: We know that resource scarcity alters cognitive processing, affecting everything from financial planning to impulse control. If we avoid discussing socioeconomic status, we risk oversimplifying findings and missing key explanatory mechanisms.

But if we can’t name the factors that shape human behaviour, we can’t design interventions that work beyond the narrowest of populations: white men (the only group of people left when those identified by terms in the banned words list are excluded).

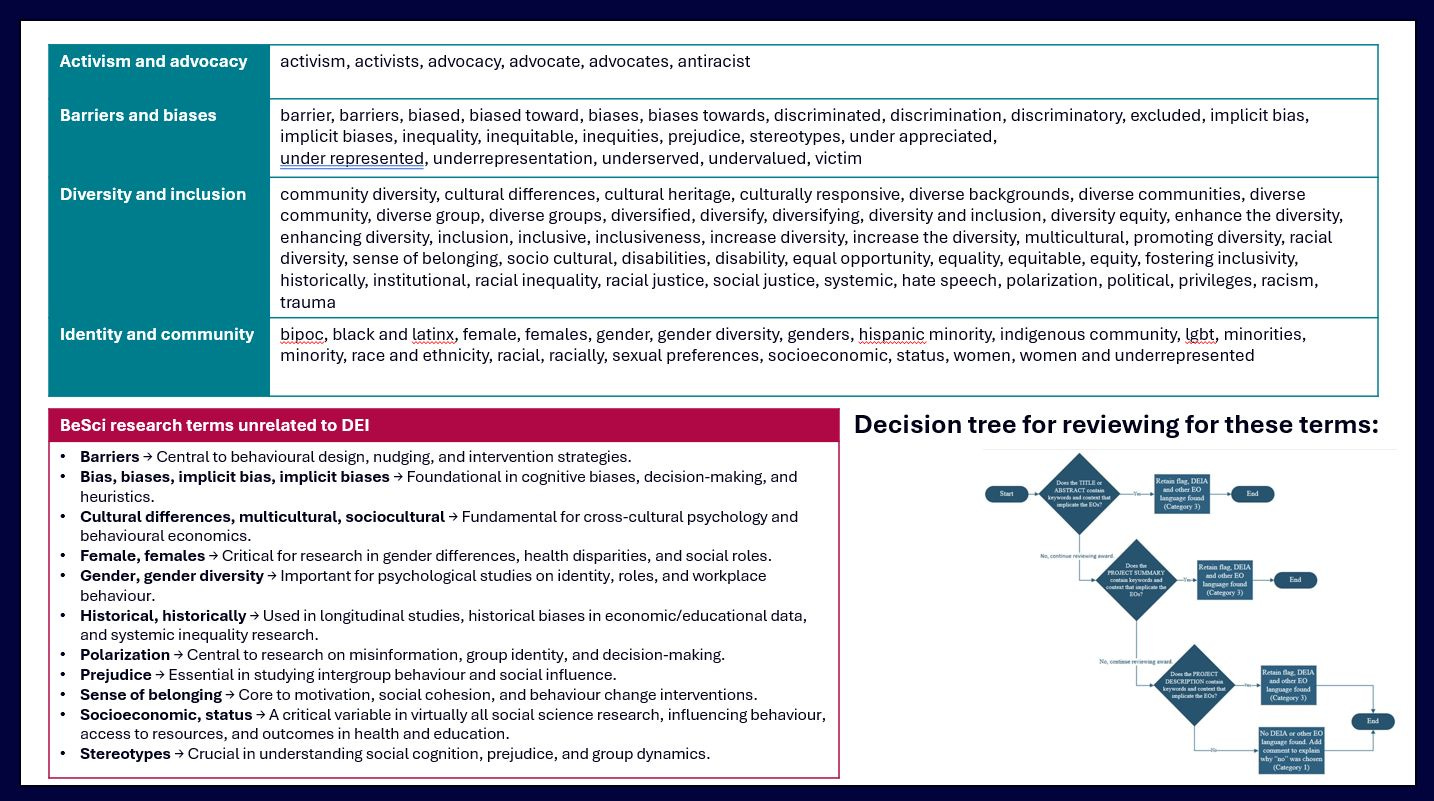

BeSci research terms included in the banned words list

Barriers → Central to behavioural design, nudging, and intervention strategies.

Bias, biases, implicit bias, implicit biases → Foundational in cognitive biases, decision-making, and heuristics.

Cultural differences, multicultural, sociocultural → Fundamental for cross-cultural psychology and behavioural economics.

Female, females → Critical for research in gender differences, health disparities, and social roles.

Gender, gender diversity → Important for psychological studies on identity, roles, and workplace behaviour.

Historical, historically → Used in longitudinal studies, historical biases in economic/educational data, and systemic inequality research.

Polarization → Central to research on misinformation, group identity, and decision-making.

Prejudice → Essential in studying intergroup behaviour and social influence.

Sense of belonging → Core to motivation, social cohesion, and behaviour change interventions.

Socioeconomic, status → A critical variable in virtually all social science research, influencing behaviour, access to resources, and outcomes in health and education.

Stereotypes → Crucial in understanding social cognition, prejudice, and group dynamics.

Implications for evidence-Based Interventions

Behavioral science informs policies and interventions in finance, health, education, and the workplace. If researchers can’t explicitly study cognitive biases, economic disparities, or social influences, interventions risk becoming less effective.

Public Policy: Governments use behavioral insights to design programs that encourage savings, improve tax compliance, and boost civic engagement. If studies can’t measure demographic factors, interventions may fail to reach the populations they aim to help.

Organizational Behavior: Companies rely on research to improve hiring practices, reduce decision-making biases, and foster diverse work environments. Without precise terminology, research on workplace behavior becomes less actionable.

Education and Learning Science: Studies on stereotype threat, growth mindset, and social belonging shape how schools support students from diverse backgrounds. Restrictions on studying cultural and economic influences could limit evidence-based improvements to education.

When funding policies dictate what behavioral science can study, real-world applications suffer. Policies designed to improve outcomes for diverse populations may become one-size-fits-all, ignoring the very factors that make interventions effective.

The global impact of scientific restrictions

Changes in U.S. policy ripple through the entire scientific community because American research influences global funding priorities, publishing standards, and collaboration networks. By shaping what research gets funded and published, these restrictions don’t just influence American science—they shape the questions asked, the populations studied, and the findings that inform global policies.

Psychology, in particular, has long struggled with a lack of global representation. The highest-impact journals are disproportionately American, and 60% of studies in top psychology journals still rely on U.S. samples, even though the country represents just 5% of the world’s population. The problem extends to who conducts and reviews research—in 2018, 54% of lead authors and 69% of consulting editors in major APA journals were based in the U.S. (Thalmayer, Toscanelli & Arnett, 2021).

At a time when psychology is only beginning to correct its overreliance on WEIRD samples, these restrictions risk reversing progress because they make it harder for researchers to study human behavior across cultures, further marginalize majority-world perspectives, and weaken behavioral science’s ability to capture the full diversity of human thought and experience.

When science loses its language

Behavioral science depends on precise definitions, clear methodologies, and the ability to measure human behavior across diverse contexts. Yet, when political constraints dictate what researchers can say, the consequences are far-reaching.

These restrictions don’t just affect U.S. institutions—they shape the entire field of behavioral science, influencing what questions get asked, which populations get studied, and how human behavior is understood worldwide. At a time when psychology is only beginning to move beyond its overreliance on WEIRD samples, limiting the language of science risks reversing progress and narrowing our understanding of human thought and behavior.

Scientific inquiry must be driven by empirical rigor, not political agendas. If behavioral science is to continue addressing critical societal challenges, researchers must be free to name and study reality as it exists—not as policymakers dictate it should be.

Read more:

How Trump's executive orders are threatening scientific research (The Week)

Exclusive: how NSF is scouring research grants for violations of Trump’s orders (Nature)

'Unprecedented': White House moves to control science funding worry researchers

NSF reexamines existing awards to comply with Trump’s directives (Science)

References

Thalmayer, A. G., Toscanelli, C., & Arnett, J. J. (2021). The neglected 95% revisited: Is American psychology becoming less American?. The American psychologist, 76(1), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000622 (open access link on page)

Webster, G. D., Mahar, E. A., & Wongsomboon, V. (2021). American psychology is becoming more international, but too slowly: Comment on Thalmayer et al. (2020). The American psychologist, 76(5), 802–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000747