When a tribute becomes a question: how the WSJ misframed Kahneman’s choice

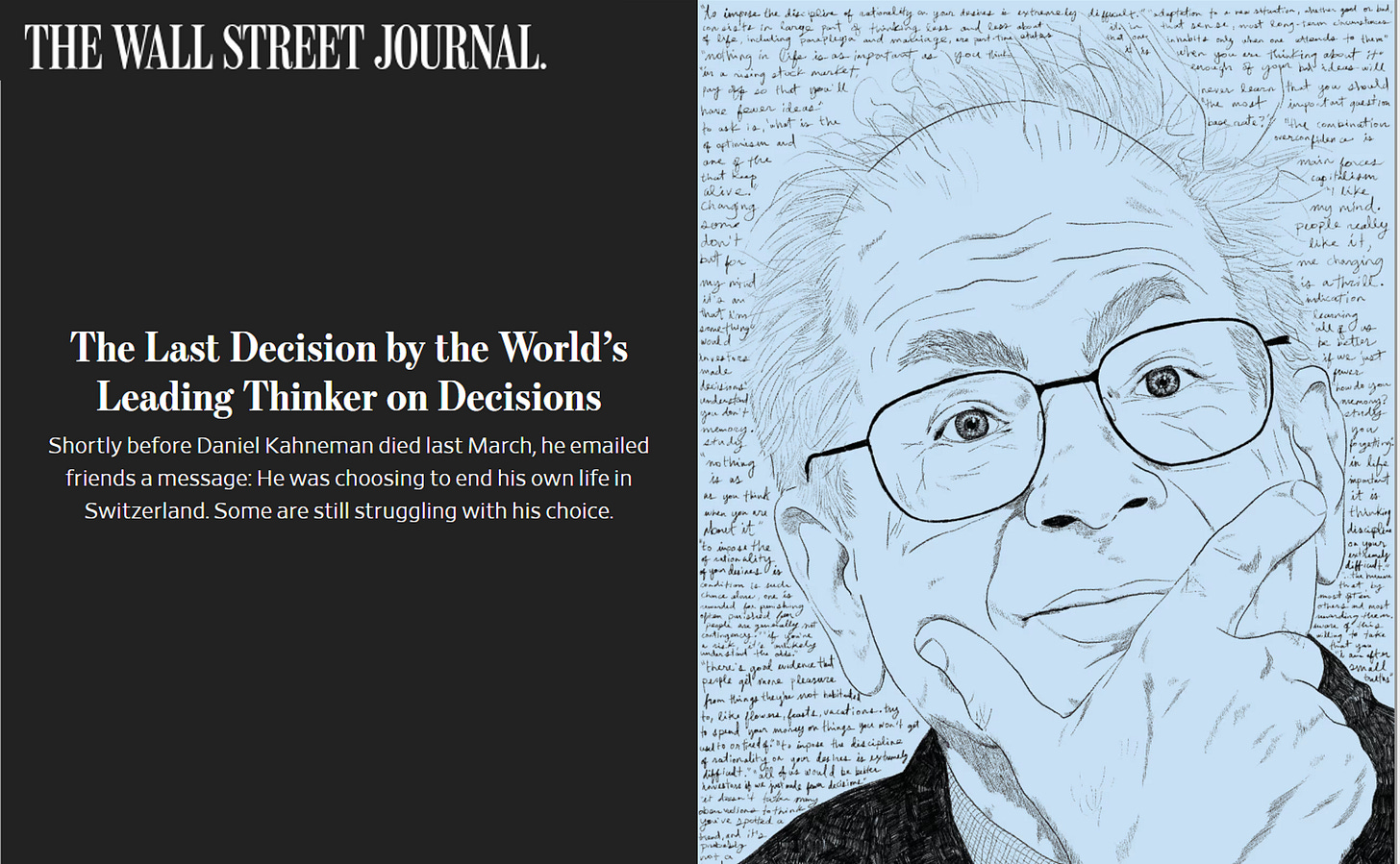

Daniel Kahneman’s final decision was his own, yet a major media outlet framed it as open to doubt—and that framing deserves a closer look.

I don’t know what Daniel Kahneman would have thought of the WSJ article. I only met him once—in a lift at a conference—but his work shaped the field in ways that opened doors for countless people, including me. That’s why it felt uncomfortable to see his final decision shaped into a debate it was never meant to be.

This should have remained a private, autonomous choice, but since it has become a public discussion, the way it is framed matters. The WSJ article has already shaped the conversation, and if that framing is left unchallenged, it risks becoming the only narrative. As such, it fails to do justice to the world’s leading thinker on decisions.

What the WSJ missed—and why it matters

When the Wall Street Journal published an article reflecting on Daniel Kahneman’s final decision, it presented itself as a tribute. Yet beneath the surface, it subtly framed his choice as something that required justification, rather than an autonomous decision made with clear intent. While it does not explicitly call his decision irrational, the article treats it as a puzzle to be solved—as if the world’s leading expert on decision-making had somehow misapplied his own principles.

Yet by Kahneman’s own account, his decision was neither a misjudgment nor the result of cognitive bias. He framed it as a deliberate choice, shaped by his values and beliefs about autonomy, decline, and what constituted a life worth living.

The issue isn’t just the article’s framing but the underlying assumption behind it: that rationality can only be understood through the lens of judgment and decision-making science (JDM).

Kahneman’s entire career challenged rigid definitions of rationality, yet the article applies the very type of thinking he spent decades dismantling. It assumes that a rational person should always prioritise longevity and subtly reduces a deeply personal choice into an optimisation problem.

This framing carries an implicit assumption: that a rational decision-maker would prioritize longevity, and that a choice to forego it must be justified. Yet Kahneman’s own work challenged the idea of a singular, objective best decision, emphasizing that context, values, and uncertainty shape human choices. The broader question this raises is not about cognitive errors—it is about whether we accept a person’s right to determine when they have had enough.

This isn’t just a critique of the article—it’s an examination of what it overlooked. We’ll explore how it misapplied decision science, ignored its own framing biases, and failed to engage with the ethical complexities of Kahneman’s decision. More importantly, we’ll examine what this reveals about how we, as a society, define rationality—and why we struggle to accept that someone might make this decision deliberately, clearly, and with full awareness of its implications.

The WSJ invented a contradiction that wasn’t there

At first glance, the article appears to honour Kahneman’s legacy, but a closer reading reveals that it subtly casts doubt on his final decision. Rather than centring Kahneman’s perspective, it amplifies the discomfort of those around him, as if their reactions inherently outweigh his well-reasoned choice. This tension creates a contradiction: the article presents itself as a tribute, yet it ultimately undermines the intellectual and personal autonomy Kahneman championed.

I -- don’t fully understand why he felt he had to go. His death raises profound questions: How did the world’s leading authority on decision-making make the ultimate decision? How closely did he follow his own precepts on how to make good choices? How does his decision fit into the growing debate over the downsides of extreme longevity? How much control do we, and should we, have over our own death?

These questions frame Kahneman’s decision as something that requires explanation—as if it were at odds with his own expertise. The underlying implication is that a leading authority on decision-making should have reached a different conclusion, one that prioritised longevity. But that assumption reflects a value judgment, not an objective measure of rationality. By suggesting that a "good" decision must lead to prolonging life, the article misrepresents not just Kahneman’s final choice, but the intellectual legacy he built over decades.

Kahneman spent his career challenging the notion that rationality consists of rigidly following universal principles. He demonstrated that human decision-making is shaped by context, uncertainty, and anticipated outcomes—not just abstract rules of optimisation. The article, however, falls into the very trap he warned against: assuming that rational decision-making always leads to a singular, objectively best choice.

The article also selectively applies Kahneman’s principles in a way that casts doubt on his decision. It quotes him as saying, “I have no sunk costs,” describing how he always prioritised evidence over past commitments. Yet it follows this by stating, “But, somehow, he couldn’t let go of a view he had formed decades earlier.”

This framing subtly suggests that because Kahneman valued changing his mind, he should have done so here—without offering any substantive reason why his long-held view was flawed. Changing one’s mind is rational when new evidence emerges, yet the article provides no such evidence that should have caused him to reconsider.

It is not unreasonable to ask whether someone has fully considered a life-altering decision. Kahneman himself emphasized the importance of revising beliefs in light of new evidence. However, the article presents this questioning as if his conclusion must have been flawed—rather than recognizing that he had already engaged in precisely the kind of reflection he advocated. It does not introduce new evidence that might have changed his mind; it simply assumes that he should have reconsidered.

This is where the article’s framing breaks down: instead of engaging with Kahneman’s decision on its own terms, it tries to fit it into a decision model he spent a lifetime proving was incomplete.

Why we feel uncomfortable about death

Kahneman had told a few of those closest to him about his plans weeks before he flew to Switzerland. Despite their efforts to dissuade him, he remained resolute. One friend pleaded with him so persistently that Kahneman eventually told him to stop. “It was a matter of some consternation to Danny’s friends and family that he seemed to be enjoying life so much at the end,” another friend recalled. “‘Why stop now?’ we begged him.” (1, 2)

These reactions, as reported in the WSJ article, reflect something deeper than personal grief—they were shaped by the way we, as a society, think about death. Humans go to great lengths to avoid confronting their own mortality. Terror Management Theory suggests that when people are faced with reminders of death, they experience existential anxiety and instinctively turn to cultural worldviews that provide structure, meaning, and a sense of symbolic immortality.

Public figures often achieve a form of symbolic immortality through their work, influence, or cultural legacy. When someone prominent dies—especially someone associated with intellect and rationality, like Kahneman—it can feel unsettling, as it serves as a stark reminder that even those who leave an enduring impact are not exempt from mortality. This is known as mortality salience: the heightened awareness of death triggered by external events. Even if the public figure was not personally known to us, their passing forces us to confront the universal nature of human finitude.

Western societies, in particular, have a death-denying culture—one that treats death as something to resist rather than accept.1 A medicalised approach prioritises prolonging life at all costs, even when it diminishes quality of life. Language around illness reinforces this resistance—people are encouraged to “battle” disease and “fight” for survival, as if accepting death is an act of surrender. Even the way we speak about death reflects avoidance, softening its reality with euphemisms like “passed away.”2

Within this cultural framework, voluntary death can be unsettling—not because it is irrational, but because it contradicts the deeply embedded idea that life must be preserved for as long as possible, regardless of its future trajectory. Psychological tendencies reinforce this discomfort. Regret aversion makes people fear that a choice was made too soon, even when undertaken with clarity. Ambiguity aversion makes the certainty of someone’s presence feel preferable to the uncertainty of life without them.

The article presents Kahneman’s decision as something that required justification, yet it treats the discomfort of those around him as self-evidently reasonable. Their reactions—however natural—were shaped by cultural narratives and psychological tendencies, not by an objective measure of rationality.

As the article itself notes:

"Aside from the potential for abuse, I think the reason for the ambivalence is obvious. If you end your life prematurely, before you are in acute pain or mental decline, you protect yourself and those you love from your imminent suffering. But you also expose your loved ones to the pain of your absence and the regret of never fully understanding your choice or why you didn’t listen to them.”

Rather than engaging with why his decision made sense to him, the article centres the perspectives of those who opposed it, implying that their unease was proof he was mistaken. This framing ignores a deeper reality: discomfort with voluntary death often reflects the values and biases of the observer, not a flaw in the reasoning of the person making the choice.

Side note: Discussions about end-of-life decisions can feel abstract until you are the one left behind. I lost my father when I was 19 and my mother at 21. While no two experiences of loss are the same, I have some personal insight into what it means to be left behind and how it shapes the way we process absence.

A decision rooted in his own principles

The article implictly assumes rationality means maximizing longevity, yet Kahneman’s own work challenged such rigid decision models. He spent decades demonstrating that decision-making is shaped by heuristics, uncertainty, and personal experience—not by strict optimization rules. His final choice reflected precisely this: an anticipatory decision based on his understanding of cognitive decline, autonomy, and what he valued in life.

The article also implies he should have reconsidered but offers no compelling new evidence to justify this. Instead, it applies decision science selectively, holding him to rational choice principles while ignoring that he spent his career demonstrating their limitations. Rather than following an abstract decision model, Kahneman made a judgment that was adaptive to his specific reality. His decision was not a failure of rationality—it was an application of it.

Kahneman’s own work provides the best lens through which to understand his choice. The article holds him to a narrow definition of rationality that he spent his career dismantling, as if rationality must always lead to the choice of continued life. Yet his research showed that decision-making is not about rigid maximization—it is shaped by context, anticipated futures, and deeply personal values.

Kahneman had witnessed the slow cognitive decline of both his wife and mother and recognised early signs in himself. These personal experiences likely reinforced his views on autonomy and control. Far from contradicting his intellectual legacy, his decision reflected the very insights he spent his life studying.

A rational choice is not necessarily the one that maximizes lifespan—it is the one that best fits a person’s circumstances, values, and anticipated future. Kahneman’s final decision was not an exception to his principles; it was a demonstration of them.

The outside view was the wrong lens

The article questions whether Kahneman followed his own principle of the outside view, stating:

Another of Kahneman’s principles was the importance of taking what he called the outside view: Instead of regarding each decision as a special case, you should instead consider it as a member of a class of similar situations. Gather data on comparable examples from that reference class, then consider why your particular case might have better or worse prospects.

It implies that Kahneman failed to do this, suggesting he did not properly assess whether people who reach 90 tend to regret decisions like his. This assumption treats longevity as the default goal, as if the only relevant comparison group is those who lived past 90. The outside view is only useful if the chosen reference class is relevant.

"A more relevant reference class might focus on quality of life rather than lifespan statistics. This perspective is already considered in fields that handle high-stakes end-of-life decisions, such as medical ethics and veterinary medicine3.

Veterinary medicine, in particular, does not just ask, “Can this animal survive?” It asks, “Is this a life worth living?”4

The ethical framework considers the animal’s perspective: Can they engage in behaviours that bring them comfort, stimulation, or joy? An active, social dog with severe arthritis may technically be able to stay alive, but if chronic pain prevents them from moving freely, interacting, or playing, their well-being is severely diminished. Veterinary ethics recognises that survival alone is not the standard for a meaningful existence.

As bioethicist Jessica Pierce, whose work focuses on how the biomedical sciences intersect with human values, writes in her book “The Last Walk”:

Why is it that we have such a revulsion against euthanasia for human beings, yet when it comes to animals this good death comes to feel almost obligatory? If it is an act of such compassion, shouldn’t we be more willing to provide this assistance for our beloved human companions as well? 5

To be clear: this comparison is not about equating humans with animals—it is about questioning why we seemingly allow animals more dignity and compassion in death than we do people.

The ethics of death and dying has long been central to philosophy. Since the 1960s, animal welfare frameworks like the Five Freedoms have recognized that sentient beings should be free from pain, discomfort, fear, and distress. Yet human medicine often focuses solely on sustaining life, sometimes without fully interrogating whether the life being extended is one the person would want to live. The assumption is that longevity is inherently good—even when it comes at the cost of independence, identity, or dignity. Kahneman’s choice seems to challenge that assumption: he was not simply weighing the possibility of living longer—he was assessing whether his future quality of life aligned with his values and expectations.

I first encountered these structured ethical frameworks when making end-of-life decisions for my own animal companions. The experience forced me to think critically about how we weigh suffering, dignity, and the right timing of death—not just for animals, but for humans. It also made me realise that these decisions require a level of selflessness. The hardest part is not centring your own emotions—your desire to hold on for longer—but accepting that sometimes, the most compassionate choice is to respect when someone decides they have had enough.

Ultimately, when you truly love or care for someone, honouring their wishes—even when it is painful for you—is an act of deep respect and kindness.

In veterinary medicine, prolonging life without considering suffering is considered inhumane. The accepted principle is that waiting until distress is undeniable often means waiting too long. Similar frameworks exist in human medicine—such as Do-Not-Resuscitate orders and palliative care—but they are typically reactive rather than proactive. Kahneman appears to have applied similar logic to anticipate future decline and make a choice before suffering became unavoidable, yet the article framed his decision as something to be questioned.

Decision science is not the only lens for evaluating choices like this. Fields such as medical ethics, philosophy, and even veterinary medicine have long engaged with questions of autonomy, suffering, and anticipatory decision-making. Instead of assuming that Kahneman’s decision was flawed because it doesn’t fit within a judgment-and-decision-making framework, we should consider that other domains could provide useful, well-developed approaches to these questions.

Kahneman’s choice is not ours to question

Daniel Kahneman’s final decision was not a contradiction of his life’s work—it was an expression of it. He made a clear-eyed, anticipatory choice based on his understanding of cognitive decline, autonomy, and the future he wished to avoid. Whether we agree with his decision is irrelevant—what matters is that it was his to make.

What is striking is that his decision was treated as something requiring validation from anyone else at all.

The unease surrounding his choice, as highlighted in the WSJ article, was never really about whether he applied good decision-making principles—it was about the discomfort of those around him, and a broader societal struggle with this topic. The article subtly positioned the reactions of those around him as more rational than his own, failing to interrogate its own biases while implying that Kahneman had somehow overlooked the very principles he spent his life studying.

Kahneman did want not present his choice as a political statement—he seemed to make it clear that he did not want his decision to become a public discussion. That, more than anything, makes the article’s framing deeply unfair. Instead of honouring his clarity, it turned his choice into something to be debated, subtly implying that the discomfort of others should have outweighed his own autonomy.

The article also took a narrow view by analysing his decision purely through the lens of heuristics and biases, as if everything could be reduced to cognitive errors even though end-of-life choices are not just a matter of decision science. They involve ethics, personal values, and dignity, so focusing solely on decision science overlooked the broader moral and philosophical dimensions of his choice.

Ultimately, we each live in our own bodies and minds. No one else can fully know what it feels like to exist in them or to anticipate what suffering may come. Recognizing that reality and acting on it is wisdom, not cognitive failure. A decision to avoid unnecessary suffering should not be reduced to a set of biases. Examining end-of-life decisions is important, but only when done with respect for the individual’s agency—not as an attempt to explain away their reasoning.

The way Kahneman’s decision was framed in the article did not sit right with me. It felt wrong that a single perspective—one that subtly questioned his clarity—should be the only one shaping how his choice is remembered. That is why I wrote this: not to argue over his decision, but to challenge how it was framed publicly, and under the guise of a tribute.

If we claim to respect autonomy, we cannot pick and choose when it applies. Kahneman made his choice with clarity. The only failure in judgment was treating it as something that needed justification—when, in the end, the only perspective that mattered was his own.

AI-generated podcast that covers both articles (any mistakes or curiosities are by NotebookLM):

Gire, J. T. (2019). Cultural variations in perceptions of aging. Cross‐cultural psychology: Contemporary themes and perspectives, 216-240.

Tradii, L. (2022). Euphemisms and the cultural framing of death: A case study in American society. In D. Ballantyne & R. Powell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging (pp. 745-760). Springer.

While human and veterinary medicine have traditionally operated under different ethical assumptions, there is an emerging dialogue about what these fields can learn from each other. For example: Selter, F., Persson, K., Risse, J., Kunzmann, P., & Neitzke, G. (2021). Dying like a dog: the convergence of concepts of a good death in human and veterinary medicine. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 25, 73 - 86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-021-10050-3./Selter, F., Persson, K., & Neitzke, G. (2022). Moral distress and euthanasia: what, if anything, can doctors learn from veterinarians?. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 72 719, 280-281 . https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp22X719681./Coombes, R. (2005). Do vets and doctors face similar ethical challenges?. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 331, 1227. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.331.7527.1227.

Deelen, E., Meijboom, F. L. B., Tobias, T. J., Koster, F., Hesselink, J. W., & Rodenburg, T. B. (2023). Handling End-of-Life Situations in Small Animal Practice: What Strategies do Veterinarians Contemplate During their Decision-Making Process?. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 1-14.

Pierce, J. (2014). The last walk: Reflections on our pets at the end of their lives. University of Chicago Press.